|

“To a Hogshead of Rum”

Frontier Commerce on the Lord’s Day:

Dupui’s General Store Ledger,

1743-1753

Abstract:

This essay announces an offbeat discovery:

a full decade of

mid-eighteenth century Sunday retail shopping on the

Pennsylvania frontier.

One might logically assume that in as much as the

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania had “Blue Laws” on the

books since 1682, along with a bevy of religious

institutions endorsing and promoting these righteous

admonitions against toil and labor on the Sabbath, that

commerce conducted on Sundays in the mid-eighteenth

century would have universally been regarded as anathema

– yet an analysis of Nicolas Dupui’s backcountry general

store ledger reveals that for the period of a full

decade, the Pennsylvania frontier routinely countenanced

instances of Sunday shopping.

This essay will serve to document this anomalous

episode and to account for those sets of causes

responsible for the rapid rise and fall of Sunday

shopping in the remote frontier wilderness of Penn’s

Woods.

ENTRIES IN THE DUPUI TRADING

POST LEDGER commenced in the early winter of 1743.

On Sunday December 15th

of that year, a number of credit-based transactions were

logged to the account of Garret Decker.

He had purchased a quire of paper, a paper of ink

powder, two papers of pins, a knife and fork set, a yard

of broadcloth, six yards of Nonesopritty and a gallon of

rum. For

Garret, this was a special day, but not because a

pre-Christmas shopping spree had secured the blessing of

presents for his wife Susannah.

As a baptized member of the Reformed Dutch

Church, Garret was keenly aware that Christmas [Kersdag]

was not a celebrated feast day and not a day specific to

exchanging gifts.

Christmas was just another day to do the Lord’s

work. So

no, this day was special for another very important

reason:

today capped off a week’s worth of Grand Opening

celebrations at Dupui’s trading post and general store.

A good two dozen of his neighbors and fellow

congregants had been there to revel in this momentous

event, and while Garret was the very first among the

faithful to shop at this well-provisioned establishment

on a Sunday, he would certainly be far from the last.

In the year 1744, Dupui’s credit/debit ledger

reported no less than nineteen Sundays during which the

store conducted business (including Apr. 5th, 1744,

Easter Sunday).

[1]

Garret’s wife, Susannah DePui

Decker, had no particular qualms about making purchases

on a Sunday.

After all, it was her father, Nicolas Dupui, the

post’s proprietor, who had erected the Old Stone Church

on the property at Shawnee-on-Delaware, who had retained

the services of the Reverend Johanus Casper Freemoutt

and who had provided the minister with a house and horse

of his own.

If her father, as an officer of the Reformed

Dutch Church, had no particular issues with opening his

store for business on the Lord’s Day, then it would be

far from apropos for her to gainsay such activity.

As a well-informed member of the landed gentry,

Susannah knew quite well that the law on this matter was

clear: “Whoever does or performs any worldly employment

or business whatsoever on the Lord's day, commonly

called Sunday, works of necessity and charity only

exempted, or uses or practices any game, hunting,

shooting, sport or diversion whatsoever on the same day

not authorized by law…”is guilty

[2].

Everybody knew the law, and

everyone knew how to turn a blind eye to the law when it

suited their purpose.

Neither would the honorable Rev. Freemoutt speak a

contrary word regarding the ills of Sunday shopping as

long as the pews of his church were filled.

The good reverend was a consummate pragmatist who

long-recognized the exasperating character of his own

congregation, a flock that just wasn’t prone to abiding

by what others might have deemed to be mandatory

religious obligations. As

noted in the "Register of the Acts, Which have been

Passed by the Rev. Consistory of this Congregation",

1741, Aug. 30.

Whereas some among us, in and outside of this

congregation, are unwilling to contribute to the

Minister's salary, and yet wish to avail themselves of

his services, it is decided by the consistory that each

person, who will not contribute to the salary of the

Minister, shall pay for a child, that they wish

baptized, six shillings, three of which shall go to the

consistory, and three to the Minister, for the

registration.

[3]

If the requisite religious duty to pay for the services

of one’s own minister was only being honored in the

breech, with the proverbial collection plate as empty as

a church on a week-day, then no Sunday sermon in Dupui’s

Smithfield plantation would ever be composed that would

serve to further rile these skinflint parishioners, such

as a timely ministerial discourse on the merits of

honoring the Third Commandment.

Congregations were like easily-spooked flocks that could

bolt in a heartbeat; they had to be properly managed by

a good and stalwart shepherd.

Already there were signs of significant

competition from the Minisink’s itinerant Moravian

ministers who would soon be preaching to “a promiscuous

audience of Swedes, English, Scotch, Irish, Welsh,

Germans, Walloons, Shawanese, Mohawks, Delawares, and

Catawbas”.

[4]

Complicating matters further,

the area’s Presbyterians were even now of a mind to

construct their own Meeting-House in the vicinity and to

share such space with the Lutherans.

While the Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s

had indeed spurred a significant religious revival,

competition was truly never good for the business of

religion, and the reverend Freemoutt had still yet

another reason to be cautiously wary:

he was currently serving in the capacity of

minister without the benefit of actually having been

validly ordained.

[5]

As such, it would most

certainly not be prudent to antagonize either this

vexatious congregation or the honorable Dupui at whose

pleasure he served.

Sunday shopping would not – at this time – be

challenged by the Church.

As to proprietor Dupui, he

was somewhat of a cantankerous old man; it didn’t pay to

get on his bad side.

Nowhere is this more clearly illustrated than in

this anecdote drawn from the travelogue of Moravian

Count Zinzendorf who on his August 1742 journey to New

York’s Mahican Shecomeco mission village secured a

modicum of respite at the Dupui home:

“In the evening we reached the bank of the

Delaware, and came to Mr. De Pui's, who is a large

landholder, and wealthy. While at his house, he had some

Indians arrested for robbing his orchard.”

[6]

Nicolas Dupui, like many of

the wealthiest Pennsylvania merchants of the day, was

evidently somewhat of a law unto himself, offering short

shrift to dictates, rules and conventions.

While others might have graciously invited the

hungry Indians in for a meal, Dupui instead opted to

charge them with theft.

It was precisely these kind of haughty

high-handed antics that would have resonated well with

Pennsylvania deputy governor Patrick Gordon (1726-1736),

a man prone to giving “huge feasts and balls,” a man who

“drank toasts, ordered cannon firings, and promoted

bonfires” and “often held these events on the Lord's

Day, much to the displeasure of strict Sabbatarians.”

[7]

A trend toward greater

secularization was being played out at the very highest

levels of government, and Dupui, a consummate

merchandiser, was quick to recognize and exploit this

emerging trend.

With the Sabbath in the Commonwealth rapidly

becoming liberalized (as evinced by those deliberately

ostentatious behaviors unabashedly on display within the

political realm), Dupui resolved that he too would play

his part in this transformative secular revolution.

That which once would have been deemed to be

conduct both thoroughly sacrilegious and unlawful was

now steadily coming to be regarded as perfectly

normative.

Dupui would see to it that shopping on Sundays

would become the “new normal” (at least on his corner of

the Pennsylvania frontier).

[8]

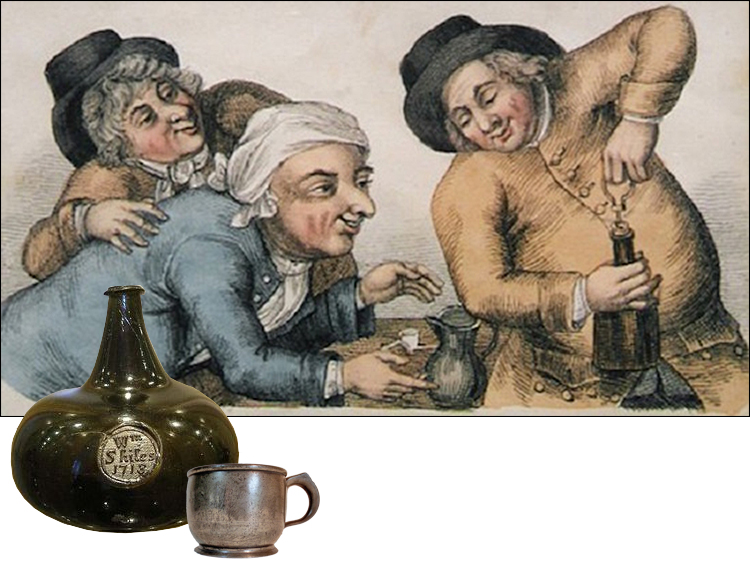

Yet in the midst of all this profound change, there was

one element that would never change – the backcountry

craving for an alcoholic brew on Sunday:

·

To a Quart of Rum for Barney

Stroud

·

To a Quart of Rum for Anthony

Maxwell

·

To a Hogshead of Rum

Containing 107 gallons for James Hyndshaw

·

To 8 Gallons & 3 Quarts of

Rum for Thomas Hill

·

To a Quart of Rum for William

McNab

·

To ½ a Gallon of Rum for

Johannes Courtright

·

To a Gallon of Rum for

Delectis

·

To a Quart of Rum for Samuel

Holmes, Sr.

All of these transactions for rum transpired on Sundays,

with the prodigious 107-gallon hogshead of rum procured

by local sawmill operator James Hyndshaw, on Sunday May

10th 1744, serving to confirm the inordinate popularity

of this commodity.

One also notes that, at this early date, Dupui’s

store apparently did not additionally function as either

a tavern or as a yaugh house.

No sales for

either rum or whiskey are recorded with pricing

reflective of drinks by the gill (a matter that would

change during the period of the French and Indian War

when the premises were occupied by a rather thirsty

company of militia).

Sales of rum during this decade were typically

for off-premises consumption as shown by this entry

found in the account of Daniel Broadhead:

“To 3 Gallons of Rum on the Raising of his

House”. As

such collective drinking was always a convivial matter,

one takes no surprise in seeing an entry in the account

of Samuel Dupui which reflected a charge of six pence

“to your part of a Quart of Rum in Company”.

The curious reader might well inquire:

was it only rum and household goods that were

purchased on Sundays, or were the purchases a tad more

expansive?

Some Sunday purchases, such as the beaver hat for Joseph

Wheeler, were for purposes of personal vanity.

Anthony Maxwell bought a pair of leather

breeches, John Burk secured a fine tooth comb and James

Walling picked up an old jacket.

Other purchases on the Lord’s Day were a bit more

substantial, such as the two hogs for John McDowell and

the horses bought by Yourian Tappen and Peter Casey.

The most

frequent transaction for commodities other than rum was,

somewhat surprisingly, for “cash”.

In this era of barter and trade, cash was still

needed for a variety of purposes, such as the payment of

rent, for official warrants and other such legal

matters, or to compensate workers.

As the area’s only cash machine, it becomes

important to recognize and credit the Dupui role as a

banking institution that served to accommodate its

clients currency needs even on Sundays.

Outlays of cash were extended to the

Schoolmaster, to Edwart Robinson’s wife, to Katharine

Rossagrance and to Allida Kuykandal, among others.

One notes with a certain amount of satisfaction

that a great many women on this frontier had their own

credit accounts at Dupui’s general store.

The store offered just about everything that a

fashionable woman of the day could desire.

Clothing and accessories ranged from a pair of

pumps and “the Remains of a pair of Stockins” (bought by

Nelly Malholen), to silk handkerchiefs, fine tooth combs

and looking glasses.

Fabrics included broadcloth, stroud, muslin,

kersey, frize, callicoe, shalloon, buckram, ozenbrigs,

garlix and linen.

A hankering for trims would be rewarded by silk

laces, gartering, sticks of mohair and assorted buttons

and buckles.

Fine furs such as beaver and fox could also be

purchased, and one could even buy (for £33) “a Negro

boy”.

Foodstuffs were aplenty and included fine and course

middlins, bran, wheat, Indian corn, peas, oats and the

occasional side of bacon.

Should one be tempted to keep a diary or

household records, quires of paper and papers of ink

powder were also available.

Then too, there is this highly revealing ledger

entry in Thomas Barrow’s account that serves to cast yet

another light on items making it into a woman’s shopping

bag: “To a

Quart of Rum your wife had”.

Truly, Dupui’s General store was a shopper’s paradise.

With everything from gunpowder, shot and lead, to

wagons, canoes, saddles and scythes, the store was the

Wal-Mart of its day, open for business seven days a

week. While

Sunday shopping admittedly tapered off somewhat after

1744, there were still numerous Sundays in 1745 in which

commerce was transacted.

In fact, Sunday shopping at Dupui’s general store

continued unabated until the autumn of 1753 at which

point it suddenly disappeared from the ledger record.

At issue is the cause responsible for the death

of Sunday shopping.

What triggered the abrupt end of this

trailblazing retail phenomenon on the remote frontier?

1752 marked the year that the

Presbyterians elected to build their Meeting-House in

Smithfield.

This one defining event had a staggeringly profound

effect: it

prompted an ecclesiastical schism within the Minisink’s

Consistory of the Reformed Dutch Church.

Up until that point, the Smithfield church had

been one of four area congregations that had enjoyed the

services of a shared minister (the others being the

churches at Minisink, Machackemeck and Walpack).

In 1753, the Consistory of Smithfield withdrew

from this arrangement.

[9]

The reason?

They now absolutely had to have the benefit of a

dedicated full-time minister in light of the local

competition that had seen the newly-built Presbyterian

Meeting-House opened up to Lutherans as well as to other

insufficiently satisfied members of the Dutch Reformed

Church.

Nothing less than an always-on-the-premises ministry

would suffice (as this was truly a war for men’s very

souls).

Church officers, such as Nicholas Dupui, understood

their fiduciary duty to safeguard the interests of the

faith, and they would perforce re-embrace all

traditional religious norms for the sake of their

Church, opting to necessarily honor all ten of the

commandments.

The days of Sunday shopping on the Pennsylvania

frontier were now officially over.

Religious values had triumphed over emergent

secularism and the Lord’s Day would continue to be

properly honored (at least until the advent of the

mid-twentieth century).

[10]

A Sunday toast to Nicolas Dupui!

Notes:

[1]

The Dupui ledger manuscript resides in the

archives of Pennsylvania’s Monroe County

Historical Association; the accounts of 167

customers that had secured credit arrangements

from Dec. 1743 to Dec. 1791 are recorded

therein.

[2]

See Neil J. Dillof, “Never on Sunday:

the Blue Laws Controversy,” 39

Maryland

Law Review, 679 (1980).

[3]

New York Genealogical and Biographical Society,

Minisink

Valley Dutch Reformed Church Records:

1716-1830 (Westminster, Maryland:

Heritage Books, Inc, 2008), iv.

[4]

William Cornelius Reichel,

Memorials

of the Moravian Church, Volume 11

(Philadelphia:

J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1870), 51.

[5]

“A meeting was held at Kingston, on Dec. 16,

1744, by the Consistory of Minisink. . . On that

day Fryenmoet was ordained validly, with the

laying on of hands by the Rev. Petrus Vas”

Ibid.

Minisink

Valley Reformed Dutch Church Records. xxv.

[7]

J. T. Jable, “Pennsylvania's Early Blue Laws: A

Quaker Experiment in The Suppression of Sport

and

Amusements, 1682-1740,”

Journal

of Sport History, FALL 1974, Vol. 1, No. 2

(FALL 1974), 120.

[8]

That Nicolas Dupui interacted at the highest

levels of government is attested to by what has

been described as “the Affair of Nicholas Dupui

and Daniel Broadhead,” a land dispute that

presaged the 1737 Walking Purchase and which was

resolved by none other than the Pennsylvania

Proprietors themselves.

See William Henry Egle, ed.,

Pennsylvania Archives, 3rd series, vol.1,

Minute Book "K" (Harrisburg, State Printer,

1894), 86.

[9]

The formal ratification of this withdrawal would

not take place until the formalization of the

Acts of Coetus of Oct. 7-14, 1755 as noted in

this extract:

“The Rev. Assembly, having heard the

reasons for and against, and having carefully

considered the action itself, found itself in

conscience bound to give the following unanimous

decision:

That, whereas it appears that the church

of Smithfield has been legally and

ecclesiastically separated from the three other

churches, the Rev. Consistory of Rev.

Fryenmoet’s three churches are, according to the

contents of the aforesaid action, obliged to pay

to the Rev. Consistory at Smithfield thirty

pounds.”

See Ibid.

Minisink

Valley Reformed Dutch Church Records, xiv.

[10]

The ledger reveals that some twenty-seven

customers on thirty-two separate occasions

availed themselves of the opportunity for Sunday

shopping.

|